Michael B. Jordan as Erik Killmonger

Erstwhile Contributing Editor Travis R May examines the connections between Marvel’s Black Panther and the ongoing debate surrounding museums and artifact collections acquired during the colonial period. This post does contain spoilers for Black Panther.

Writer/Director Ryan Coogler’s first foray into the Marvel Cinematic Universe, 2018’s Black Panther, is a fairly radical film. This is appropriate, given the character’s origins in the 1960s, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. The film’s vision of the Afrofuturist nation-state of Wakanda—which, in the continuity of the MCU, avoided colonial exploitation and expropriation at the hands of the European powers and ultimately turned into a thriving metropolis by dint of access to a rare natural mineral resource known as vibranium—is a dramatic rejection of centuries of racist Western denigration of African peoples and culture. A year after its release, it is clear that this premise resonated with wide audiences, as the film still looms large in the zeitgeist. It earned more than $700,000,000 in its domestic theatrical run, beating out fellow Marvel star-studded heavyweight Avengers: Infinity War for the 2018 box office crown,[1] and more recently it has been nominated for seven Academy Awards, including in the Best Picture category—a historic first for a superhero/comic book adaptation film.[2]

Perhaps the most radical figure is the film’s villain: N’Jadaka, better known as Erik Killmonger, played by Michael B. Jordan. Killmonger, the orphaned son of a Wakandan prince, raised in anonymous exile in Oakland, has been disaffected by the racism and prejudice endemic in his adopted country. His service as a soldier of the imperialist American state in foreign wars has only deepened his cynicism, setting him on an irrevocable path of violence. Although there are several stages in his scheme, Killmonger’s basic plot is to stage a coup against his long-lost cousin (our titular protagonist, a.k.a. T’Challa, played by Chadwick Boseman) in order to procure the Wakandan throne and access to the bleeding-edge military resources of the Wakandan state, which he then plans to distribute to guerilla sleeper cells embedded in major cities across the world. The tables turned, these groups will launch what will effectively be a race war against the white colonialist powers in a great struggle for Black liberation. The audience is expected to be horrified by this prospect, and to root for T’Challa to prevail in this struggle (his plans involve massive foreign aid programs to other African countries and Black diasporas, and reconciliation and cooperation with the West rather than violence). But, perhaps surprisingly, the film goes to some lengths to make Killmonger into a compelling villain with complex and even tragic motivations. After the film’s premiere, the hashtag #killmongerwasright trended on Twitter. Clearly, even viewers without a working knowledge of Frantz Fanon’s theories regarding decolonization and the necessary catharsis of violent opposition to the inherent and fundamentally genocidal violence of settler colonialism found something to admire in the sheer audacity of Killmonger’s rebuke to the neoliberal, imperialist, and predominantly white supremacist world order.

Setting aside the film’s intriguing decision to portray its central drama as a cross between a Shakespearean family tragedy and a rumination on the philosophical disagreements that created a gulf between the non-violent and armed resistance wings of the American Civil Rights Movement, it is Killmonger’s introduction at the fictional “Museum of Great Britain”—a thinly veiled analogue of London’s famous British Museum—that has perhaps provoked the most internet think pieces.[3] It is worth watching and dissecting in full for its shrewd commentary on racial politics (Killmonger, as a black man in a predominantly white space, is immediately profiled by museum security, for example), but suffice it to say that the scene culminates with an accusatory Killmonger questioning a museum curator about the provenance of West African artifacts on display. When informed that the pieces are not for sale by the indignant curator, he belligerently (but astutely) responds: “How do you think your ancestors got these? You think they paid a fair price? Or did they take it, like they took everything else?”

The (real-life) British Museum.

Coogler’s decision to fire shots across the bow of one of the world’s premiere museums—not in a small, awards season art film or a documentary, mind you, but in the biggest blockbuster action film of 2018—is a rather stunning and bold development, but also one that is sophisticatedly reflective of cultural trends. Museums, regarded by most in Western societies as benign repositories of artifacts and knowledge, have come under increasing scrutiny of late—and not merely from revolutionary sources (Killmonger is, after all, the villain of the story, and we are here again meant to disagree with his violent methods), but from academics, the media, and affected indigenous peoples. The question of how to preserve and display artwork, artifacts, and even human remains that were acquired (or, more often, looted) by Europeans, primarily during the height of European and American imperialism between the eighteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, is an extremely thorny ethical issue.[4] The British Museum and leading institutions in France, Germany, and the United States have, for the most part, a sordid track record when it comes to addressing these concerns, much less rectifying them, but recent trends suggest that this issue is gaining wider and wider recognition and support—perhaps in part due to the critical and commercial success of Black Panther—and that museums are finally beginning to feel pressure to address these concerns.[5]

Since the release of the film last February, a number of prominent art and artifact sales, public protests, and government studies and decisions have taken place with bearing on the issue.[6] Some, such as the private sale at Christie’s of an Assyrian relief from King Ashurnasirpal II’s Northwest Palace at Nimrud in modern-day Iraq, represent depressing business as usual. Despite backlash from academics against the sale of the item by Virginia Theological Seminary, which had held it since the 1850s, it fetched over $30,000,000 at auction—a figure three times the initially valued amount, possibly (as Columbia University Professor Zainab Bahrani asserts) because the destruction of the palace itself by ISIS insurgents between 2015 and late 2016 created scarcity in the market for these pieces.[7] The relief went to a private buyer who unsurprisingly chose to remain anonymous, likely because this person did not want to be associated with ISIS’s enslavement and murder of several thousand women and children that helped boost the value of their new piece. Virtually no consideration was given to the cultural heritage of the relief as a vital piece of Iraq’s history. Nor was this the first instance of the robbery of Iraq’s cultural heritage that came about as a result of disastrous US foreign policy blunders: in the aftermath of the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad was looted, and evidence suggests that sales of these pieces on the black market went on to support global terrorism.[8] Collectors turned a tidy profit, but at an enormous cost for the people of Iraq. Such is the will of free market capitalism.

In other recent cases, a number of activist organizations and African and Asian nation-states have confronted the governments and museums of Western countries, with mixed results. In December 2018, a guerrilla “Stolen Goods Tour” of the British Museum was conducted by the activist group “bp or not bp?”, which takes issue with the long-term sponsorship of the British Museum by bp (formerly British Petroleum), because the group believes that the arts are tainted by association with the deeply immoral operating practices of the fossil fuel leviathan.[9] The tour highlighted a number of artifacts that were acquired through violent or illicit means by British diplomats, explorers, and military or naval personnel, including the Gweagal Shield, an Aboriginal Australian wooden shield that was taken by James Cook’s first landing party at Botany Bay in 1770 after they shot its original owner.[10] Other items that were featured in the Stolen Goods Tour or are otherwise being held controversially by the British Museum include the Parthenon (or Elgin) Marbles[11] and the Benin Bronzes,[12] as well as a colossal, four-tonne Moai statue known as the Hoa Hakananai’a that the people of Easter Island have repeatedly requested the return of, explaining that it is an incredibly important spiritual artifact that is understood to contain the soul of the Rapa Nui people of the island.[13]

The Hoa Hakananai’a Moai.

The British Museum’s response to these requests and demands has followed a pattern. Basically, they will not entertain requests for permanent restitutions. This is, at least partially, the result of an Act of Parliament passed in the 1960s, around the time of the formal dissolution of the British Empire: this act prevents the Museum from deaccessioning items in the Museum’s collection outside of two very special circumstances—in the case of human remains (a complicated issue we will return to below), or in the case of artworks stolen from Jewish owners by the Nazis during the course of the Holocaust.[14] Items seized during Britain’s long period of imperial dominance in the formally or informally colonized world quite often do not fall under these parameters. In order to soften this blow, however, the British Museum consistently presents itself as a “leading lender,” offering to temporarily loan out items for short-term exhibitions in the countries they were acquired from. The British Museum officials also emphasize the benefits of their stated mission as an institution that presents the breadth of human history by exhibiting these artifacts as “ambassadors” for various cultures that reach mass audiences (as many as 6 million people passed through the museum’s doors in 2017, for example).[15] Their seemingly noble goal, to bring awareness and appreciation for these artifacts and their diverse creators to mass audiences, rings hollow in light of the fact that it often runs counter to the expressly stated wishes of the indigenous peoples to whom these artifacts originally belonged—to bring them home, once and for all, as part of their cultural heritage. In this sense, it is nothing more than a form of coercive cultural imperialism. In fairness, however, it must be noted that since the new year, the British Museum, the Victoria & Albert Museum, and the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford have all announced plans to hire full-time staff positions that will evaluate collections for stolen or otherwise problematic colonial artwork. Part of this process will involve updating exhibits with “very honest” labels and explanations that reveal the true circumstances of the exploitation and expropriation of the pieces. These are, admittedly, small steps, and a far cry from a commitment to formal return, but they are evidence that the museums are beginning to feel compelled to answer the rising public pressure to be more transparent about their collections and acquisition practices.[16]

The Parthenon (or Elgin) Marbles

Some recent news is more promising, however. In November 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron agreed to the return of 26 statues and thrones held in the Quai Branly Museum in Paris to the modern-day state of Benin in West Africa.[17] These items had been stolen from the Kingdom of Dahomey after the colonial conquest of 1892, and represent merely a handful of the more than 46,000 items in the museum’s African collection that a recent report described as having been obtained under some degree of duress. The Ivory Coast, another former French colonial possession in West Africa, has subsequently requested the return of 148 works from France as well. While Macron has been at least somewhat receptive to the idea of these proposals, the director of the Quai Branly Museum, Stéphane Martin, is deeply critical of the proceedings, complaining that “everything that was collected and bought during the colonial period” has been tainted by the recent report with “the impurity of colonial crimes.”[18] Martin contends that some of the collections were acquired through scientific expeditions or private purchases, and that these should be held separately from artifacts and items obtained through violent or coercive means (although the mechanisms for effecting this evaluation remain murky at this time).

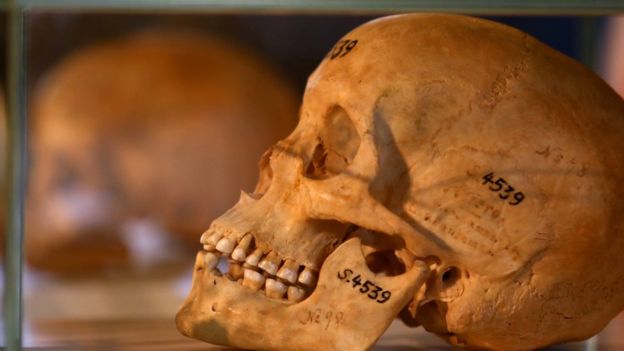

The related issue of the restitution of human remains has also gained public prominence since the turn of the century. During the colonial period, vast numbers of skulls of indigenous peoples were bought or more often stolen in the colonies and sent to museums and universities in Europe and America. In the most horrific cases, such as in the aftermath of the Herero and Nama Genocides and the Maji Maji Rebellion in German South-West Africa and German East Africa respectively, these skulls had belonged to the direct victims of German colonial violence (and, on several occasions, Herero and Nama women imprisoned in concentration camps were forced to prepare the skulls for transport by taking the decapitated heads and flaying them of their skin with shards of glass before boiling them).[19] In the past two decades, the descendants of the survivors of this colonial violence have lobbied for the return of the skulls of their kinsmen. This process has been fraught with complications. Although there have been restitutions of some skulls from German museums and universities to Namibia, Tanzania, and Cameroon, sometimes accompanied by formal handover ceremonies (but not—as of yet, anyway—a formal apology and restitution plan from the German government), thousands more remain in Germany.[20] Similarly, the Natural History Museum in Paris still has over 18,000 skulls of various ethnicities in its collection.[21] And, although several hundred Maori skulls held in American and British institutions have been returned to New Zealand in recent years, some institutions have held out against this restitution trend. Despite its own written policies, for example, the British Museum has refused to return a number of Maori and Torres Islander skulls held in vaults deep underneath their campus at Russell Square to their respective peoples, stating that “it was not clear that the importance of the remains to an original community outweighed the significance and importance of the remains as sources of information about human history.” This has generated alarm and derision from activists and academics alike, who have quite correctly pointed out that the “research” value of these skulls was never anything more than a white supremacist colonial-era fantasy and therefore totally “bogus,” as they had been collected as part of the long-discredited branch of racialist pseudo-science known as phrenology or craniometry. Other academics and curators have observed that there is virtually no evidence that meaningful scientific research has ever been conducted using these vast collections of skull specimens.[22] Sadly, this restitution process is likely to last well into the twenty-first century, and it seems just as evident that some institutions will resist all efforts to participate in the restitution process at every turn.

A human skull from Namibia with a German catalogue number

Finally, it should be noted that there is also the possibility that new technologies might ultimately help non-European peoples in their quest to retrieve stolen artifacts from foreign museum collections, but reason to be skeptical about the long-term prospects for success of this initiative as well. Recent strides in 3D scanning and printing technology, for example, have led to discussions about the feasibility of creating printed models for use in the museums, while allowing for the restitution of the originals back to their country and/or people of provenance. In many cases, the institutional weight of museums has pushed back against this idea, denying access for researchers who would like to begin the process of scanning and digitizing collections. This has led to what might be termed guerrilla museum research. In 2015, for example, Nora al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles supposedly surreptitiously scanned a bust of Queen Nefertiti contained in the Neues Museum in Berlin with cell phones, and then used the data to print a 3D model that they put on display in Egypt.[23] Described as “the most ethical art heist” in history, this model has opened up the possibility that similar feats could be accomplished with other stolen or appropriated artwork and artifacts. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Neues Museum was unamused by this scheme, and Germany (like many other European countries) continues to display “a conservative and proprietary view” of its collection. The ideal, obviously, would be for museums to participate in the scanning process, and then return the original while keeping the printed model, but for now many museums remain apparently hostile to the possibility of even allowing 3D scans to be taken for the purposes of creating a model to be provided to those seeking a restitution of the original artifact. A sea change will likely need to occur before most museums begin to perceive participation in digital scanning and 3D model creation as their best option for ethically maintaining the integrity of their exhibits.

In summary, it should be clear that the museum as an institution is not and has never been a merely neutral or beneficent holder and displayer of objects and artifacts. Much to the dismay of museum boards across the world, it has become a pivotal battle ground in the ongoing struggle for decolonization, and against Euro-American white supremacy, as indigenous and formerly colonized peoples strive to reclaim material pieces of their looted cultural heritage. This is not to go so far as to state that the museum as an institution should be abolished, of course—there are certainly arguments that it can serve as a useful educational tool, and especially if museums make a genuine effort to openly and honestly present the troubled past of their acquisitive practices while working with partners across the world to permanently return important pieces to local institutions—but it is well past time for a reckoning that addresses the myriad ways that museums have been and often continue to be the beneficiaries of violent European expansion and exploitation across the globe. Black Panther is neither the first piece of art that has expressed this concern, nor will it likely be the last, but its phenomenal success and cultural reach has no doubt brought this topic of conversation to a wider swath of the public than any before.[24] For that, it should be commended, and Coogler’s work should serve as a reminder that popular, blockbuster fare like superhero films need not merely serve the lowest common denominator of audience expectations: they are capable of raising important questions amidst the bombast and the pageantry and the costumes.

[1] https://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=marvel2017b.htm.

[2] https://variety.com/2019/film/in-contention/oscars-black-panther-becomes-first-superhero-movie-ever-nominated-for-best-picture-1203113451/.

[3] https://news.artnet.com/art-world/black-panther-museum-heist-restitution-1233278; https://hyperallergic.com/433650/black-panther-museum-politics/.

[4] http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/2017-10/19/content_33436716_2.htm; https://www.rct.uk/collection/2105644/looty-the-pekingese. The examples of immoral colonial period looting are far too many to identify individually, but perhaps highlighting one especially brazen example is instructive: when, during the Second Opium War in October 1860, British forces stormed, looted, and burned the Qing Emperor’s Summer Palace, they carried off with them several million artifacts and pieces of artwork, along with the first Pekingese dog to ever be brought to the British Isles (she was found in a dresser drawer by the British troops, and was subsequently presented by the commander of the expedition as a gift to Queen Victoria, an avid dog lover, who appropriately enough decided to name her new pet “Lootie”). In 2017, UNESCO estimated that over a million of these relics were still held abroad in the collections of 47 museums, primarily located in Europe.

[5] This is not to suggest that museum curators are necessarily complicit in the questionable activities undertaken by the institutions that employ them. It should also be observed that curators, for the most part, are deeply invested in their work, and value the artifacts under their care while respecting the cultures that produced these items. Questionable acquisition policies and decisions to avoid difficult discussions about deaccessioning artifacts often take place at much higher levels within these institutions.

[6] My thanks to Sarah Luginbill, Ph.D. Candidate in the CU Department of History, for drawing my attention to many of the articles cited below.

[7] https://hyperallergic.com/469108/31-million-sale-of-3000-year-old-assyrian-relief/?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=November%205%202018%20Daily%20-%20After%2031%20Million%20Sale%20of%203000-Year-Old%20Assyrian%20Relief%20Experts%20and%20Artists%20Denounce%20Christies&utm_content=November%205%202018%20Daily%20-%20After%2031%20Million%20Sale%20of%203000-Year-Old%20Assyrian%20Relief%20Experts%20and%20Artists%20Denounce%20Christies%20CID_75d664320ee595a3c0e765c457b74b3d&utm_source=HyperallergicNewsletter&fbclid=IwAR2AwkYn5n5eJzHxBiTRdj_ajRJJzaJ9f2cc2SkAYiZf9E1SsHLNoqHe9EQ

[8]https://www.palmbeachdailynews.com/news/local/loot-from-iraq-museum-financed-terrorism-recovery-mission-leader-says/ix2EYiJh8U79Az9MWrSE9N/.

[9] https://bp-or-not-bp.org/.

[10] https://hyperallergic.com/475256/hundreds-attend-guerrilla-activist-led-tour-of-looted-artifacts-at-the-british-museum/?fbclid=IwAR2QUMa-MC2GL8d0MMkjSgBDeCDLHyn6bzR5AxJ4sW39c1rH02sjokncqNY. The activist who gave a presentation on this topic, Rodney Kelly, is a direct descendant of Cooman, the shield’s original owner. In his talk in the museum’s “Enlightenment Room”, in front of a display case containing the shield, he explained the spiritual significance of the artifact to his people.

[11] The Parthenon Marbles were acquired in the early 19th century by the British diplomat Lord Elgin, who acquired permission to take the magnificent friezes out of the ruined Parthenon from the Ottoman Turkish authorities (Greece was, at this time, a part of the Ottoman Empire). In 1816, the British Museum purchased the stones from Elgin. Since achieving independence in 1832, Greece has attempted via diplomatic, political, and legal avenues to retrieve the Marbles from London—so far, entirely without success. This has not stopped the Greek government from building special display cases in the Parthenon Museum that sit empty, awaiting the return of the artifacts that may never come home. Despite the controversy, the British Museum rationalizes Elgin’s decision to take the marbles as prudent given the possibility of their being damaged through vandalism, arson, or natural erosion (the building had been destroyed in the 17th century when a gunpowder magazine exploded), and they argue that he was entirely within his legal rights to do so because he acquired permission from the Turkish rulers. This remains a controversial issue. In 2014, UNESCO offered to mediate between the two sides, but the British Museum declined on the technicality that they were an institution, not a government.

[12] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/06/20/bringing-home-benin-bronzes-nigeria-open-loans-rather-permanent/. Nigeria has been requesting the return of the Benin Bronzes literally since it became an independent nation-state in 1960. Recently, the Nigerian government has shifted strategies and now has declared that it is open to a solution based around temporary lending of the Bronzes.

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/nov/20/easter-island-british-museum-return-moai-statue?fbclid=IwAR2S9zsr5SOf6OGRKwy-AzxRQEmbACVLYrwf48iVjfo3b_Ssau2HwjvbXLQ.

[14] https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm199900/cmselect/cmcumeds/371/0060805.htm; http://www.elginism.com/similar-cases/the-british-museums-de-acessioning-policy/20080516/1114/.

[15] https://hyperallergic.com/475256/hundreds-attend-guerrilla-activist-led-tour-of-looted-artifacts-at-the-british-museum/?fbclid=IwAR2QUMa-MC2GL8d0MMkjSgBDeCDLHyn6bzR5AxJ4sW39c1rH02sjokncqNY.

[16] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/01/01/uk-museums-task-staff-identifying-stolen-colonial-collections/?WT.mc_id=tmg_share_fb&fbclid=IwAR25enCo7OMIK_ZqLT8mI8kjImebQkmjT1tHOSGCrWCxTKUFKHGzkZNydGI.

[17] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-46324174?ns_campaign=bbcnews&ns_mchannel=social&ns_source=facebook&ocid=socialflow_facebook&fbclid=IwAR0qzrX6i9JQcmBKOWWUmpG_YvfCUfeMs1F7CzqU5kRHTk2aOh-D9pL2P-g.

[18] https://news.artnet.com/art-world/ivory-coast-148-works-from-france-1426252?utm_source=facebook.com&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=news&utm_content=everyday-news&fbclid=IwAR0V6ayzlBLqSDbQ-Tmsa6ddwH82H93iGSF7I97Kw64Zlx2tu_5pXo8_1kQ.

[19] https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-troubling-origins-of-the-skeletons-in-a-new-york-museum.

[20] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-45342586.

[21] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/03/france-museums-restitution-colonial-objects.

[22] https://news.artnet.com/market/its-not-just-art-that-indigenous-peoples-want-back-from-museums-they-want-their-ancestors-human-remains-too-1397737?utm_source&fbclid=IwAR3t3sUHbsi9AT8RCo54Ie3Dhy2LhtbPRHXSyNXkcOlT0Pvg5Av7tz3USoU.

[23]https://news.artnet.com/art-world/restitution-and-technology-2018-1420246?utm_source=facebook.com&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=news&utm_content=everyday-news&fbclid=IwAR05DzqE1zdh2smCVCtFoG8l-eQfwLvFR-BcLyNC2jQzsUV22f45vNGT4QQ. I say “supposedly” here because some experts believe that the pair managed to acquire a pirated version of the museum’s own digitized scan of the bust, rather than completing the scan themselves on the sly. In either case, the data they acquired allowed them to produce an accurate replica.

[24] For example, both Lynn H. Nicholas’s book The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War (1995) and the eponymous film adaptation from 2006 delve into the subject of how museums have struggled with the issue of disposing of artwork procured from Nazi looters from victims of the Holocaust.

Pingback: Genteel Spoliation: Decolonization at the museum and Marvel’s Black Panther – The Present and The Past