Contributing Editor Travis R May delves into the history behind Operation Finale, a recent film depicting the capture of notorious Nazi war criminal Adolph Eichmann in Argentina in 1960. This post does contain spoilers for the film.

The historical record and the 2018 film Operation Finale agree on the basic facts: on the night of May 11th, 1960, a Mossad and Shin Bet commando squad ambushed Adolph Eichmann during his regular commute home in the darkened outskirts of Buenos Aires. After a brief roadside struggle, Eichmann was bundled into a waiting getaway car and driven to a prearranged safe house, where he was kept in isolation—and sometimes under sedation—for ten days before the Israeli government managed to smuggle him out of Argentina on an El Al flight. The goal had always been to capture the escaped Nazi alive so that he could be charged for his crimes against humanity—and more specifically against the Jewish people of Europe—at a highly publicized trial in Israel. Notwithstanding the dubious legal claims upon which this extralegal rendition of a German citizen from a sovereign South American nation-state rested, the mission was a rousing success.[1] Eichmann’s subsequent trial exposed a new generation to the horrors of the Holocaust, and although the movie does not show the audience Eichmann’s hanging in May 1962, it is quite clear that his conviction and execution is all but a foregone conclusion.

So far, so good. The devil, though, is in the details. Operation Finale, like virtually all historical films and period pieces, can perhaps be excused for casting photogenic actors (heartthrob Oscar Isaac plays Peter Malkin, the man who wrestled Eichmann into a ditch and later procured his confession) to play average-looking historical figures, and for inventing a love interest for our protagonist to pine over. These are, in the grand scheme of things, minor cinematic sins, virtually forced on all films just by the conventions the medium.[2] Where the film jumps the shark into more blatant fabrication, however, is in its depiction of the Nazi subculture of the German expatriate community in Argentina, and most problematically of all in its portrayal of Eichmann himself.

Oscar Isaac as Mossad agent Peter Malkin in Operation Finale

It is undeniable that Argentina became a safe haven for Nazis and other fascists who sought to escape justice following the collapse of Hitler’s “Thousand Year Reich” in 1945. Many of the “ratlines” set up to help fleeing SS officers evade justice, including the one used by Eichmann himself, were aided by the Argentine security services as well as by Catholic officials, who helped them procure new identities and passport documents before putting them on slow boats to South America.[3] Once they had arrived safely in Argentina, they were protected by the government of Juan Peron, notable for its fascist sympathies. The Argentine government refused to consider legal extradition requests from the West German government, ruling that Nazi war crimes and crimes against humanity were “political” in nature and therefore not subject to existing treaties.[4] As such, the escaped Nazis felt safe enough to set about the mundane tasks of creating new lives (sometimes under new identities—Eichmann was known as “Ricardo Klement” during his Argentine exile). Eichmann was aided by German contacts in securing work once he arrived in Argentina in 1950. Many of the Nazis also eventually sent for their families in Germany or Austria. Eichmann’s wife Vera and his three sons joined him in 1952.[5]

The film, in the interest of heightening the drama of Eichmann’s capture, interrogation, and extradition, takes the very real evidence of Argentina’s favorable attitude toward the Nazis and escalates it to an absurd degree. The film version of Eichmann, at the behest of fellow Nazi Carlos Fuldner, is urged in the days before his capture to lead the Argentine Nazi community in an attempt to take over the national government. Later, after Eichmann is apprehended by the Israeli team, the film Nazis launch a massive operation to find him, brutally torturing witnesses by carving Swastikas into their flesh, peeking leeringly into seemingly every window in greater Buenos Aires, and eventually discovering the safe house only seconds after the Mossad squad has frantically exfiltrated with Eichmann in tow. Finally, the El Al flight smuggling Eichmann out of the country is delayed and nearly stopped at the airport by a call from an Argentine soldier to the chief of police, who alerts the Nazis and then helps them race to the airfield. The plane lifts off and our heroes just barely escape in time, thwarting the Nazi rescue attempt.

All well and good for a dramatic finale, except that none of the above events seem to have transpired at all. Eichmann’s disappearance was of course noticed by his family, and his Nazi-sympathizing sons attempted to locate him without any success, but there is no evidence that the greater Nazi community mobilized to locate Eichmann. This appears to have been the case for several reasons. Eichmann was apparently not very well liked by his fellow Nazi escapees, and was considered something of a whiner who complained constantly that he had not been able to personally enrich himself during the Holocaust, among other things. He was also by no means their leader, and in fact was not even especially personally prosperous during his decade in Argentina. He seems to have stumbled from low-paying job to low-paying job, working at one time as a surveyor, at another as a failed laundry manager, and he was employed in a Mercedes-Benz factory as a welder and then a foreman at the time of his capture.[6] He and his family lived more or less in squalor on Garibaldi Street in San Fernando, sometimes generously described as a neighborhood but at the time really nothing more than an impoverished backwater north of the Argentine capital. They did not have running water, indoor plumbing, or electricity in the house he had built there, and a large part of the reason he was so easily captured by the Israelis is that his walk home every night from the bus stop was across an unlit, empty dirt field surrounded by open ditches.

Ben Kingsley as SS Obersturmbannführer Adolph Eichmann in Operation Finale

None of these facts are consistent with the film’s portrayal of the Nazi war criminal. Ben Kingsley’s Eichmann is an urbane, sweater-wearing villain of considerable intelligence whose Nazi colleagues hold him in reverence. He then plays a cat-and-mouse game with his captors, even when he is placed in the humiliating position of being strip searched and forced to request assistance when using the toilet. He is by turns disarmingly friendly and grotesquely menacing, and he refuses to cooperate with the Israelis unless they divulge personal information about whom they lost to the Nazi genocide (in Malkin’s case, his sister and her young children). Kingsley and Isaac’s scenes together aim for the psychological horror resonance of Clarice Starling’s interview with Dr. Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs, and theirs is a deeply personal relationship at the core of the film. Kingsley’s Eichmann is, more or less, the sophisticated but sociopathic serial killer of a thousand Hollywood films that have come before.

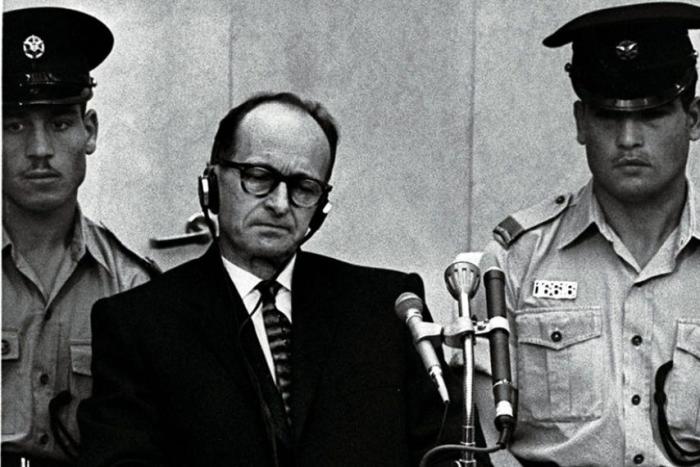

The chief problem with this characterization of the man sometimes described (although perhaps not entirely accurately[7]) as the “architect of the Final Solution” is that it totally disregards what philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt called “the lesson of the fearsome, word-and-thought-defying banality of evil.”[8] Arendt, who reported on Eichmann’s trial for The New Yorker and later published her famous (and enduringly controversial) work Eichmann in Jerusalem, argued that Eichmann was neither cultured nor an ideologue nor a rampant anti-Semite by nature. Instead, she asserted that Eichmann, a high school dropout who failed in virtually every enterprise unconnected to his SS service, was a joiner who parroted Nazi slogans and clichés on cue but who had very little internal intellectual life to speak of. He was a functionary without much in the way of his own beliefs and opinions; nothing more than a bureaucrat. In other words, from Arendt’s perspective, the true horror of his actions—sending hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of European Jewish victims to misery and death in the concentration and extermination camps—is not that they were born of a deviant mind, but that they were the product of an ordinary one in a society that had been warped and bent to a ghoulish purpose. Eichmann was a dull man looking for a purpose, and he had found one in the administration and management of one of history’s greatest crimes not because he was an aberration, but because he was so fundamentally and uninspiringly normal.

The real Eichmann on trial in Jerusalem, 1961

Some historians, of course, have taken issue with Arendt’s analysis of Eichmann’s personality and character for a variety of reasons.[9] Whether or not one agrees with Arendt or her critics, it is apparent that Operation Finale is not interested in exploring this particular question of historiography, instead trading on well-worn tropes of maniacal geniuses playing psychological games with their adversaries. As such, the film squanders a unique opportunity to plumb the depths of true evil, for whomever or whatever Eichmann was in his heart of hearts, his utter lack of empathy and the amount of pain and destruction he wrought should continue to leave us with troubling questions about the nature of the human condition.

[1] Neal Bascomb, Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World’s Most Notorious Nazi (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009), 84-85. Ironically, given its later record regarding extraordinary renditions, the CIA had declined to help the Israelis extract Nazis from Argentina, stating “We are not in the business of apprehending Nazi war criminals.” On the contrary, U.S. intelligence services had spent the immediate postwar period instead recruiting valuable Nazi scientists and officials such as rocket scientist Werner von Braun as part of “Operation Paperclip.”

[2] This is not to suggest, however, that film as a narrative medium is uniquely shackled by convention. Television, plays, poetry, and novels are also, to one degree or another, shaped by these same considerations. And, as a colleague of mine perceptively observed upon reading this piece, academic disciplines are hardly free from these same constraints and considerations. For example, the historian Hayden White argued that works of history are commonly structured according to the “emplotments” of comedy, romance, tragedy, and satire. In other words, it would seem to me that humans tend to express themselves via archetypes, tropes, and conventions in all but the most avant-garde of their creations. It brings to mind the famous lamentation in Ecclesiastes 1:9; perhaps there truly is “nothing new under the sun.”

[3] Bascomb, Hunting Eichmann, 70-72.

[4] Bascomb, Hunting Eichmann, 123. Prior to the discovery of Eichmann, a request to extradite the notorious Dr. Josef Mengele, the camp doctor of Auschwitz who performed horrific experiments on Jewish captives, was denied by the Argentine authorities. Tipped off by the authorities, Mengele easily escaped and was never brought to justice: he drowned after suffering a stroke while swimming on vacation in the resort town of Bertioga, Brazil, in 1979.

[5] Bascomb, Hunting Eichmann, 79.

[6] Bacomb, Hunting Eichmann, 117.

[7] Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (New York: The Viking Press, 1963), 84. Eichmann, for example, was not involved in the mass shootings undertaken by the Einsatzgruppen that made up a large part of the first phase of the Final Solution. He also was the lowest ranking official in the room at the infamous Wannsee Conference of January 1942. His expertise in rounding up Jews and transporting them via rail lines to the death camps should not be overlooked, of course, but he did not actually oversee the extermination camps either. His superior, Reinhard Heydrich, seems to have been much more influential in orchestrating the Holocaust up until his assassination in mid-1942 by Czech and Slovak partisans (the subject of another recent film, Anthropoid).

[8] Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, 231.

[9] Some have accused Arendt’s overarching theory of totalitarianism of obscuring the actual facts of the case. Others have contended that the Sassen Papers, a series of interviews conducted by a Dutch Nazi-in-exile with Eichmann in the mid-1950s that were not published until long after Eichmann’s execution, reveal that his true character was much more viciously anti-Semitic than he let on during the trial.