Contributing editor Julia Frankenbach considers the importance of early western American literature for academic historians and for a politically engaged American public. In this moment of political confusion, facts begin to ring hollow. The broader truths and guiding ethics in the writings of our western American forebears may help as we seek the way forward. The views expressed in this piece belong solely to the author.

Chumash-Chicana artist Sarah Biscarra Dilley‘s sup, sup, sup, sup (land, ground, year, dirt). Biscarra Dilley’s art most recently appeared in Visions into Infinite Archives, an exhibit curated by Black Salt Collective at the SOMArt Cultural Center in San Francisco. Her work celebrates Chumash knowledge and culture while depicting the harsh realities of California Indian experiences after missionization in the place that became California.

PROLOGUE

This is a difficult week. The outcome of the 2016 U.S. presidential election has challenged many global citizens’ basic expectations for leadership and social progress. Donald Trump’s victory is particularly unsettling for those who love and study the Mexico-U.S. borderlands. The President-elect’s diplomatically unintelligent demands—a physical 2,000-mile wall meant to separate Mexico from the United States, to be financed by Mexico, tops the list of outrageous proposals—violate the sensibilities of educators, writers, artists, historians, informed inhabitants, and all others who draw sustenance from the rich, multiethnic history and culture of the American borderlands, a region that, for many, includes northern Mexico. Historians shake their heads in particular disbelief at Trump’s continued tendency to use incorrect or entirely fabricated information in interviews and speeches. It is difficult to nurture hope for improved integrity of this nation’s historical memory in a political environment saturated by aggressive falsehoods. The daily contrast has proved wearying, but, for me, it has also sparked new questions—and some uplifting answers—about the nature of fact, fiction, truth, and the business of each in the study of (and the love for) American history.

As an historian in training, my immediate reaction to what seems an onslaught of misrepresentation has been to get tougher with my facts, check dates, practice lines of argumentation. Most days, this exercise seems a logical response to the President-elect’s outspoken disregard for factuality. But at times, the response also seems a slight to the discipline I love, for it generates the same combative, blow-by-blow language to achieve the same small goal: proving the “correctness” of a point of view. Academic history is capable of a great deal more than this. As many understand, its power is not in its encyclopedic capacity, and, certainly, its mission is not merely to distinguish between “what happened” and what did not. To the contrary, I think the ultimate potential of academic history is in its ability to persuade a readership into interconnectivity and care. Master historians, in other words, have figured out the art of turning many facts into a few truths, through the vessel of story.

In his book, fittingly titled Not by Fact Alone: Essays on the Reading and Writing of History (1989), John Clive pays homage to nineteenth-century French historian Jules Michelet’s vision for the discipline:

As far as [Michelet] was concerned, the whole point of writing history was to re-create a past that not only could, but must, be used—eventually by the historian’s readers, but in the first place by the historian himself—to satisfy his own psychic and spiritual needs, and to inspire him both to bear witness to past virtues and to do his share in the rooting out of present evils.[1]

The trick of history, then, is not in the organization and deployment of facts but in the transformation of facts into broader ethics that can sustain us personally and guide us collectively. During this despairing political moment, I find myself yearning for pieces of writing that defend the histories I know not with that same return-fire of dates, details, and specifics, but with the more constructive, affirmative, broadly persuasive tools of literature. Three days after his election by American voters, Trump’s erroneous statements pervade the land. It is a good time to seek solace in the land of fiction.

MEXICO, CAPITAL OF THE NORTHERN INDIES [2]

Young Pedro Sarmiento enjoyed his first journey outside the walls of Mexico on a late spring day in 1788, shortly after his graduation from the College of San Ildefonso.[3] Fresh with pride for his newly won title—Bachelor of Arts, ad omnia—Sarmiento journeyed to the hacienda with his parents’ wealthy ranching friend, Don Martín, to observe the spring livestock branding. Sarmiento enjoyed his view of the corral, but he did not enjoy what the view afforded him. The event’s roughness, particularly the workers’ many injuries, unsettled him, and he leaned in to speak his nerves to the elderly curate who shared his bench.

“Father,” he ventured, “is that how rational beings act, exposing their lives to be sacrificed by an enraged beast? And do so many people troop in to enjoy the blood of the brutes spilled, and perhaps even that of their fellow man?”

The sage curate affirmed Sarmiento’s doubts and commended the young graduate for his moral judiciousness. Indeed, the curate continued, the base passions stirred by the branding corral also drew crowds to the violent bull fights in Mexico. This vilest of Spanish customs would continue on in Mexico “until at last we forget [it], as repugnant to Nature as it is to the enlightenment of the century in which we live.”

Despite Sarmiento’s genial exchange of ideas with the curate, he became distracted from the elder’s counsel over the course of his stay, turning instead to strutting among his peers and pulling pranks among his male friends. Don Martín’s sister banished Sarmiento from the rancho when his flirtations became intolerable.[4]

This sequence of events signifies the pattern that would come to characterize the remainder of Sarmiento’s life in New Spain. As he grew older, Sarmiento, or “El Periquillo Sarniento,” as his swaggering schoolmates nicknamed him, continued to show great intellectual and moral potential, but he also continued to smother his chances for improvement by indulging his pride and lack of discipline.[5] Periquillo’s frivolous education left him unprepared for his father’s death. Lacking trade skills and any knack for thrift, he turned to crime and deceit, learning the muddy geography of the Mexican streets, taverns, and pulque stands. He injured innocent people when he falsely advertised as a doctor and a judge. Banished to Manila, he resolved to change but relapsed upon his return to Mexico, joining a band of highwaymen. When he and his gang nearly committed murder, Periquillo’s epiphany finally came. He reformed his ways in time to become a father and head of household, and he finished his days counseling his children on the value of a different kind of education—one based not on blind absorption of European beliefs but instead on the lessons of practical experience in Mexico.

La Memoria de Nuestra Tierra (The Memory of Our Land), a 10-foot by 50-foot digital mural created in 2001 by Judy Baca for the Denver International Airport. The mural depicts Colorado’s Hispano-Mexicano heritage, giving special emphasis to the experiences of families as they crossed through Juarez-El Paso and took work on American railroads. Image from http://www.judybaca.com.

While it is a fictional one, Periquillo’s history is deeply significant to the borderlands. Published in 1816 by Mexican criollo José Joachín Fernández de Lizardi, El Periquillo Sarniento was Hispanic America’s first novel and remains a foundational Mexican literary text. By emphasizing the systemic social decay of the colonial environment, Lizardi advocated political independence to a generation of Mexicans grown tired of New Spain’s dysfunctional administration. With Periquillo’s foibles, Lizardi also expressed the difficult contradictions inherent to revolutionary thought in early nineteenth-century New Spain. The War for Independence (1810-1821) required Mexicans to reject paternalistic patterns of Spanish rule, but this, Lizardi argues, was an inherently difficult task for a generation of criollos whose Catholic faith was tied to reverence for the monarch and whose potential for leadership had been stunted by the effeteness of Spanish education and by centuries of economic suppression of the Mexican-born. Appearing in serial installments in Mexico City newspapers during the War for Independence, Periquillo gave moral pardon to revolutionaries whose rejection of authority may have seemed recklessly disobedient and destructive. Periquillo’s descent into delinquency, Lizardi showed, would prove a necessary step to independence and redemption, a metaphor the author hoped would encourage his readers to support the independence movement. At the novel’s end, an aged, feeble Periquillo recounts his youthful mistakes to his children. With this closing image, Lizardi folds Periquillo into his hopes for new unity among the Mexican people. As Periquillo addresses his children, Lizardi addresses his readership in familial terms. He leaves them with a reassuring vision of a male-headed family, promising new, masculine Mexican leadership and absolution for the original crime against the father.

El Periquillo Sarniento is deeply moving. Its grief is sincere; its humor is ruinous. And its exposition is incredibly vivid. Lizardi anchors the elegance of his satire and the loftiness of his political vision in the leaden, degraded conditions of early nineteenth-century Mexico City. My favorite element of the exposition is Lizardi’s careful reconstruction of the city’s diverse patterns of speech. Indigenous Spanish, gambling slang, and criminal lingo all find their way into the text, which, in result, voices multiple social classes and the forms of striving inherent to each. With regard to this last point, Lizardi finds special amusement in the tendency of the city’s amateurs to badly imitate European discourses. Scientific and legal terminology, French rhetorical courtesies, and Latin turns of phrase all suffered dismemberment on the tongues of partially educated Mexicans, a quirk that Lizardi preserves, celebrates, and mocks.

Untitled piece by contemporary Southwestern artist Jade Antoine.

Reading Periquillo brings the borderlands to life. As Lizardi’s protagonist travels the literary geography of New Spain, readers begin to understand its present-day corollary—the American Southwest—as an evidently pluralistic place, defined less in terms of the two modern nation-states that came to control it and more in terms of relationships that spanned nations and cultures. Periquillo places Mexican literacy and Mexican struggles at the heart of the borderlands’ story. Lizardi’s expressions of frustration and hope for his Mexico—a Mexico that encompassed present-day California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and parts of Colorado, Oklahoma, and Kansas—are poignant and familiar, and they productively scramble dominant narratives of Southwestern history, which usually begin in 1848, with the region’s annexation by the United States.

But, the historian replies, do these things make Lizardi’s work literature? To some, El Periquillo Sarniento looks more like a primary source than a work of literature. The work certainly does serve in this capacity—to the same extent that Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) and Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and other satirical novels do. The question itself reveals an underlying set of assumptions about what constitutes literature in the present-day U.S. Why is it that a list of works by Homer, Swift, Hawthorne, Cooper, Hemingway, Thoreau, and Poe looks like literature, while a list of works by Cabeza de Vaca, Lizardi, Yellow Bird, de Burton, Winnemucca, and Martí looks simply like a list of primary sources? Why is one group’s work of literary value, while the other’s remains merely literal?

All pieces of literature—which we might here define as written works of exceptional rhetorical skill and stylistic power that in some way advance our understanding of the human condition—serve, in some capacity, as windows onto the past. But those works that receive wide readership also continue to speak very loudly in the present. A literary “canon” encompasses the stories and themes that reflect for a society what it considers to be its defining struggles. As a living source of instruction and inspiration, therefore, the canon actively reproduces the historical consciousness of the culture that gave rise to it. Literature, in other words, is a key cultural component of memory.

El Periquillo Sarniento is a satirical novel in praise of a nascent Mexican nationalism. It does not uphold in any way the sovereignty of the United States in the American West and, therefore, it has no place in American-literature-as-usual. But if American high school students read works translated from Spanish and French, written by indigenous people, Mexicans, Mormons, Asian Americans, African Americans, Muslims, and others in varying degrees of enfranchisement, they might be much better equipped to challenge falsehoods concerning our collective heritage–and, therefore, the nature of our common debt and obligation.

Perhaps by attention to the power of literature, historians may begin to define a world in which academic history enters mainstream conversations more fluidly. Perhaps those of us in graduate school can envision careers in collaboration with public education policy officials. In our classrooms, perhaps we can share pieces of literature that, with our histories, teach a common transnational past. There is more than one way to appreciate a piece of early western literature. One can harvest many facts from Periquillo; it does indeed tell us a great deal about northern New Spain in the 1810s. But its truths—about the longings and achievements of Mexican nationalists and the broad scope of North American struggles for liberty—also satisfy. How can we begin to embrace works of literature on their own terms, not simply as grist for the many mills of our own story-telling profession? The writings of Spanish and French colonists, Nuevo Mexicanos, Californios, Native Americans, and all the other people of the borderlands ought to be raised up among us, for public enjoyment and benefit, as part of our group project. Let them speak too, with us and our stories.

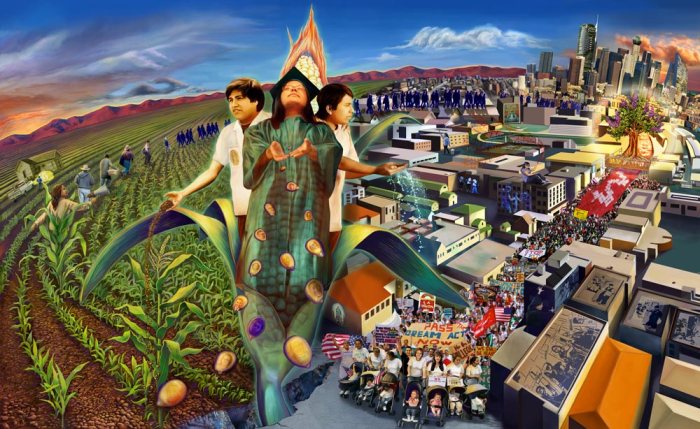

Gente del Maiz (Corn People), an 18-foot by 33-foot digital mural placed in the Miguel Contreras Learning Complex of downtown Los Angeles in 2012. The mural is the result of a 20-week collaboration between Professor Judy Baca, her students at the UCLA@SPARC Digital/Mural Lab, the UCLA Labor Center, and high school students of the Miguel Contreras Learning Complex. The mural expresses themes from the testimonies of students and parents at the Miguel Contreras Learning Complex and aims to promote memory of immigrants’ struggles, senses of belonging and power in American society, education and public engagement among the descendants of immigrants, and empowerment of Latina women. Image from http://www.judybaca.com.

Many early western writings are of deep literary and cultural value, particularly for a contemporary American readership still largely unfamiliar with the early, fundamentally mixed-race histories of the place that became the American West. Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca composed his Relación in the mid-1500s. The rhetorically elegant account is a good example of the “chronicle,” a popular genre among an elite Spanish readership that coveted works of this kind for their “creative power.”[6] Xicoténcatl, published in 1826, is an anonymous historical novel about the events leading up to the conquest of the Aztec empire. It gives eloquent voice to an anti-Spanish perspective and is particularly intriguing for its idyllic historical understanding of the indigenous world.[7] Cherokee writer Yellow Bird wrote his novel, The Life and Adventures of Joachín Murieta, the Celebrated California Bandit (1854), in the wake of the United States’ appropriation of California. The first novel published in California, Joachín Murieta received wide acclaim and helped to initiate “borderland literature,” a nineteenth-century genre that pondered postbellum ethnic tensions and the struggles of mixed-race people in the borderlands.[8] For more ideas, an excellent source is the Western Literature Association’s phenomenal online syllabus exchange. The myriad syllabi on this website demonstrate remarkable breadth with respect to place, people, and time period. Dr. Keri Holt’s English seminar “Hispanic American Literature, 1500-1900: From Colonies to California” is decidedly transnational in scope and describes her hopes for a more “transamerican” understanding of U.S. literature. The other syllabi are equally creative and exciting.

If our greatest truths do, indeed, lie in our fictions, as Alan Charles Kors urged in his 1998 lecture “Birth of the Modern Mind,” then I take some solace today in the creative, questioning words of the people who preceded me in this region. Fictions guide us all—those who hope for integrated, equitable societies, and those who would advocate return to what they perceive as a once-“great” Anglo-Saxon monoculture. As we seek the way forward, through a loudness of false facts, we would do well to become better acquainted with the truths in all of our fictions.

NOTES

[1] John Clive, Not by Fact Alone: Essays on the Writing and Reading of History (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1989), 32. Originally quoted by Aaron Sachs in Aaron Sachs, “Letters to a Tenured Historian: Imagining History as Creative Nonfiction—Or Maybe Even Poetry,” Rethinking History 14 (2010): 32.

[2] This phrase appears in José Joachín Fernández de Lizardi, The Mangy Parrot: The Life and Times of Periquillo Sarniento, Written by Himself for his Children, translated and edited by David Frye (1815; Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2005), 7.

[3] During the late colonial period in New Spain, “Mexico” was the proper term for present-day Mexico City. The precise year of Sarmiento’s graduation is unclear in the text of El Periquillo Sarniento. I have ventured a guess here, based on Lizardi’s approximation of the date of his protagonist’s birth (somewhere from 1771 to 1773) and the age of Sarmiento’s female companions during his stay at the hacienda (fifteen years of age). If Sarmiento was of comparable age, the fictional year would have been between 1786 and 1788.

[4] I derive the details for this narrative passage from Lizardi, The Mangy Parrot, 15–23.

[5] The nickname “El Periquillo Sarniento,” or “The Mangy Parrot,” mocked Sarmiento’s yellow-and-green school uniform. “Periquillo” is a diminutive form of “perico,” a word that described a small parrot associated in Inquisition records with free speech, blasphemy, and lasciviousness. The nickname also defiled Sarmiento’s surname with its reference to sarna (mange, or bodily filth). See footnote #10 in Lizardi, The Mangy Parrot, xiii.

[6] Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, The Account: Álvar Núñez Cabeza De Vaca’s Relación [in description of journey from 1528 to 1536], translated by Martin A. Favata and Jose B. Fernandez (Houston: Arte Público Press, 1993).

[7] [Anonymous], Xicoténcatl: an anonymous historical novel about the events leading up to the conquest of the Aztec empire, translated by Guillermo I. Castillo-Feliú (1826; Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999).

[8] Yellow Bird, Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta: Celebrated California Bandit (1854; Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1955).

Pingback: Facing Up to Canada’s Colonial History in Gord Downie’s “Secret Path” | Erstwhile: A History Blog

Really nice writing, Julia, as always. After the election, I wanted to take my mind off of current events; so one book I read was “Empires, Nations, and Families: A New History of the North American West, 1800-1860,” by Anne F. Hyde. And it’s all about borderlands–about constantly shifting power between extended families, between nations of established Natives and intruding Euro-Americans, among the peoples at the edges of distant rising or falling empires. And it’s about those “mixed-race histories of the place that became the American West” that you mention. And I couldn’t escape current events (as I should have expected). Throughout the book there were examples of “journalists” engaging in “fake news” to stir up racial and ethnic hatred–worse than today, really, because the propaganda led directly to the destruction of many people’s lives. Your essay here extended my thinking about these places and times into literary, fictional realms. I look forward to reading more of your work.

Andrew: thank you for your kind words. I am pleased that you mention Dr. Hyde’s work. I read Empires, Nations, and Families about a year ago and was impressed and moved by Hyde’s achievement. I am especially drawn to her insight that both intercultural and personal relationships underlay diplomatic developments in the early West. I think your insights on the parallels between the mid-19th-century West and our own current world are spot-on, and I am pleased and touched that you found useful connections between my writing and the broader set of social and political transformations Hyde describes. Thank you for writing–and, especially, for reading!

Pingback: The (Award Winning) Erstwhile Blog Entries of 2017 | Erstwhile: A History Blog

Pingback: A Fiction Reading List for Summer 2017 | Erstwhile: A History Blog